"Law Isn't Real": When a Floundering Democracy No Longer Believes in Constitutional Order

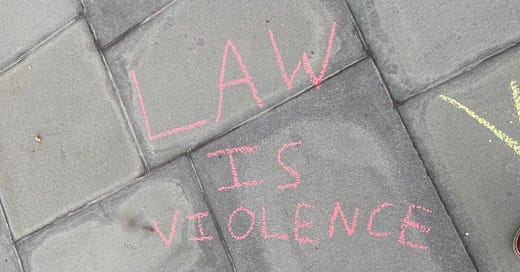

The political nihilism rising now is the death knell of free society.

On September 4, 1932, the Weimar Republic of Germany enacted far-reaching policies aimed to lower workers’ wages, implement a means test and slash funding for unemployment insurance, and cut taxes for corporations and the rich.

While the substance of these laws may sound familiar to the ears of a Westerner in 2022, their method of enactment is somewhat less so. These policies were not passed into law by the Reichstag (Weimar’s equivalent to parliament or congress). Instead, they were promulgated by one man, German Chancellor Franz von Papen, under powers invoked by President von Hindenburg through Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. Article 48 contemplated the use of temporary dictatorial powers in case of emergency. The Article reads in part:

If public security and order are seriously disturbed or endangered within the German Reich, the President of the Reich may take measures necessary for their restoration, intervening if need be with the assistance of the armed forces. For this purpose he may suspend for a while, in whole or in part, the fundamental rights provided in Articles 114, 115, 117, 118, 123, 124 and 153.

This was not the first time Article 48 had been invoked by the president to grant the chancellor emergency dictatorial powers. In fact, in the Weimar Republic’s short life, emergency powers were invoked more than one hundred times. Increasingly, Article 48 came to be seen as a routine tool to circumvent the impotence of a dysfunctional Reichstag incapable of or unwilling to legislate or govern as the president and chancellor wanted.

Nor was this the last time Article 48 was invoked. Even if we never learned the details and legal minutia, nearly 90 years later adults across the world are familiar with the result of President von Hindenburg’s famous invocation of Article 48 in February 1933 to grant emergency dictatorial powers to the German chancellor newly appointed to succeed von Papen (after a German general’s brief stint in the office)—Adolph Hitler.

The Weimar Constitution was never officially dissolved in Hitler’s lifetime. The Nazi government codified its dictatorship with the Enabling Act (enacted, of course, under Article 48). Article 48 and the Enabling Act functioned as a proverbial rubber stamp, “enabling” total Nazi rule for all 12 years of Hitler’s thousand-year Reich. This political theater continued even after President von Hindenburg’s death, whereupon Hitler dissolved the office of the presidency entirely (under, you guessed it, Article 48 and the Enabling Act). The theater finally ended in April 1945 at the end of Hitler’s pistol, which he turned on himself with the Red Army overtaking Berlin.

Power vs. Constitutional Order

In a country like the United States, does law stem from the pure exercise of power or from constitutional order? This is a relatively abstract point of academic discussion, but periodically the public takes popular interest in the question. The latest swell of interest has been stoked by the leaked Supreme Court draft opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which if published will overturn Roe v. Wade and remove the federal guarantee of abortion rights to women nationwide. The uproar and collective frustration on the political left has invigorated overnight the sentiment that our constitution specifically and the laws that govern our country broadly “aren’t real” and that the only thing that matters in law is the exercise of power.

A professor of constitutional law at Georgia State tweeted as much to his more than 30,000 followers:

Bill Maher echoed this sentiment to an even larger audience last week in his May 6 episode of Real Time, saying:

It’s not really about the laws or the constitution. Whenever I see a lawyer, whether it’s on TV or in an ad, anywhere, they’re always in a room with an entire wall of law books behind them. An entire wall. It’s what you fucking think. What you feel, and then you’ll find something in that wall of books to back it up.

I truly sympathize with this perspective, but it is ultimately wrong. And embracing it is equal parts foolish and dangerous. Much like currency, law is a human construct. But that doesn’t mean it’s “not real.” Law is less tangible and more tenuous than other human constructs, but it is quite real. The different laws written to govern different societies across the globe demonstrably produce different results in practice. Hitler tried and failed to overthrow the Weimar Republic in a pure exercise of power during the Beer Hall Putsch, and it landed him in prison. But the government was impotent and ineffectual. Released after serving 9 months of a 5-year sentence, Hitler realized he would need to come to power through the rule of law set forth by the Weimar Constitution. And that’s what he did. This is precisely why the modern-day Federal Republic of Germany, having learned hard lessons from the rise and fall of Hitler’s Third Reich, significantly curbed executive power in its constitution.

And yet, the Weimar Constitution did not intend for Article 48 to bring about a permanent dictatorship. Its abuse and overuse (and public apathy) transformed it. Closer to home, constitutional metamorphosis has been comparatively less stark in the United States. For all our faults, we have never constitutionally assented to open dictatorship. One could argue that this is due to the fact that the framers of our constitution were already fearful of executive power, which is reflected in the delicate checks and balances built into our three “co-equal branches of government.” Still, the executive branch today enjoys more power than the Constitution ever contemplated. And ‘judicial review,’ the Supreme Court’s power to review constitutional questions, was established by the Court itself, not within the four corners of the Constitution.

What of our latest source of unrest? The draft opinion overturning Roe v. Wade implicates stare decisis, the legal doctrine that judicial rulings should be based upon existing precedent, which should not be overturned except in extraordinary circumstances. Stare decisis, however, does not require the Supreme Court to stick to existing precedent no matter what. If that were true, the Court could never have overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, which held that racial segregation was constitutional. Nor could it have ever overruled Baker v. Nelson, which held that the constitution didn’t protect same-sex couples’ right to marriage. Stare decisis is a complicated doctrine, and necessarily so to account for the competing needs of stability of law on the one hand and constant-but-gradual societal change on the other.

Stare decisis is a procedural doctrine, but modern discourse cares very little for the nuances of procedure. Instead, partisans are obsessively devoted to results-oriented thinking. The political left didn’t feel that law was fiction when Brown v. Board of Education overturned Plessy or when Obergefell v. Hodges overturned Baker. And if overturning Roe leads the left to feel that law isn’t real, the holding in Roe itself spurred the same sentiment on the political right. According to those and other critics, the constitutional right to privacy enshrined in Griswold and extended in Roe is completely fabricated. And yet, in 2008 those same critics celebrated the Supreme Court’s invention of an individual right to unregulated gun ownership in District of Columbia v. Heller, an interpretation of the Second Amendment dreamed up and peddled by the NRA to increase gun sales.

The Willful Erosion of Constitutional Guard Rails

The truth is, modern partisans want law to be power. Stare decisis when it suits your goals. Judicial activism when your side holds the court. Appeal to these principles is couched in sophisticated arguments, but it is carefully selective and ultimately stems from convenience in order to reach some political goal. In our viciously partisan sociopolitical landscape, opponents’ victories are increasingly seen as exercises of pure power, justifying equal and opposite exercises of pure power. And the danger is, the more society embraces this jaded view, the more it becomes true.

The right has long sought to cloak political opponents on the left in the trappings of communist totalitarianism. Now the modern left increasingly labels any political goal of the right as “fascism.” The decision to overturn Roe and leave the question of abortion to elected legislatures is cast as “anti-democratic.” The cynical modern thinker pretends to see no difference between out-and-out dictatorships and constitutional governments overstepping and widening their reach.

And in an act of tragic irony, the behavior engendered by that view over time gradually, inexorably, causes the difference to fade, hit an event horizon, and ultimately vanish.

Constitutional order does not establish impenetrable hard lines. What it does do is generate various sources of inertia and guard rails to dampen the exercise of power. Even when one party controls both houses of Congress and the presidency, it does not enjoy a dictatorship. It inevitably passes the reins of power to the opposing party, knowing that party will not have a dictatorship either.

The embittered ideological fervor capturing both sides of American politics today is driving us toward an event horizon now. Our obsession with law as power will take us over it. Students at Yale Law, the most prestigious law school in the country and the school with the most influence on our laws and government, seem to be relishing the thought:

Democratic republics tend to collapse into dictatorships. Sometimes the erosion of constitutional order takes centuries, as with the Roman Republic. Sometimes it takes decades, as with the Weimar Republic.

Germans living in the 1920s and early 30s jaded by the expedient partisan erosion of constitutional order may have seen the ever-increasing use of Article 48 decrees as a sign that “law is power” and constitutional order wasn’t real. Those Germans who lived through the Third Reich and witnessed true rule through the pure exercise of power, however, learned the difference.